Michelle Greenblatt passed away October 19, 2015. We hope our tribute issue honors her.

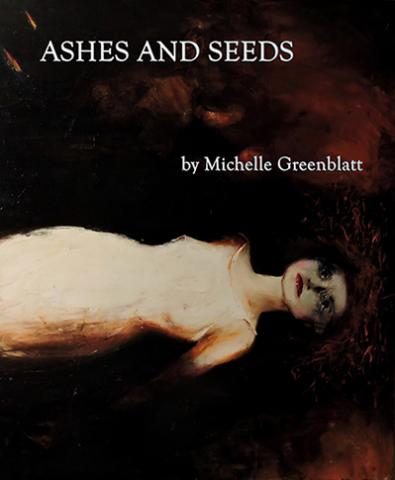

At long last, Unlikely Books is the proud publisher of the second single-author full-length poetry collection by Michelle Greenblatt, ASHES AND SEEDS!

Michelle Greenblatt, who became the Poetry Editor of Unlikely Stories: Episode IV in 2013, has spent nine years developing this 166-page narrative, exploring the horrors, potential and actual, of teen sexuality. Please enjoy this reading from the book:

And consider what people are saying about ASHES AND SEEDS:

"'Streaks of Scarlet: a Story in 100 Parts, the longpoem that opens ASHES AND SEEDS, reads like a nightmarish fairy-tale; chock-full of butterflies, bones and beheadings—where there's bloodsap leaking from the deviltrees. Greenblatt's lurid imaginings and macabre motifs will no doubt haunt each reader as they themselves amble down this embrangled path called life, in search of answers."

—K. R. Copeland

"With clarity of intention, her compelling artistic devotion focusing on respiring light into unseen environs through summoning interior stimuli, Michelle Greenblatt has createdASHES AND SEEDS, an aggregation of breath and rhythm that pulse across spectral meaning into declaration of presence and reality. Through central elements dealing with what makes existence an ocular component, these texts transfigure through their innovative collocations, which create and document form delving beyond predefined figure, to explore and contemplate language as source of progressive philosophy."

—Felino A. Soriano

"In ASHES AND SEEDS Michelle Greenblatt writes from the raw-nerved vantage of a Dante without a guide's protection about her entrapment in a hellish world dark as a waking nightmare. Her surrealistic visions virtually offer no escape except language itself, whose double-edged nature dissipates some threatening experiences while giving sudden presence to others, sometimes in the same passage. Greenblatt's unsettling landscape conjures Burroughs, Lautreamont and Genet, using an adventurous sensibility that challenges the boundaries of the prose poems and haibuns that express her condition and her attempts to embrace or escape it. This excellent work from a poet with a unique voice and vision comes highly recommended."

—Vernon Frazer

"ASHES AND SEEDS reveals that poetry is the bravest act. A narrative voice in 'Screaks of Scarlet' announces that 'She hikes out to meet her edges.' The story is replete with evidence of an unfathomable capacity of said being to remain in the state of terror. ASHES AND SEEDS ennobles its creator as a powerful inventor of paths envisioned to provide nanoseconds of relief from 'the horror.' Roles are never simple; they blur, are shared. They proliferate and swivel, such that every being performs every role, in succession and simultaneously. The voiced presence of a speaker anticipates, with uncanny depth, a range of signals from distance and dimensions. Each presence complicates then forms new fears. The figure anger fuels, demands, retrieves, relives, reviles, reforms, resurfaces. And in 'the intoxicating venom of betrayal,' a miraculous suspicion lives the act of finding holiness beyond known anchor points turned dust. No reader comes away breathing the same way after being here. No reader comes away."

—Sheila E. Murphy

Or the introduction by the editor, Jonathan Penton:

If you read books on the history of 20th Century poetry (stay with me folks, it's something that some people do), whether written at the time or since, you’ll find a broad desire to avoid discussing the Confessional movement. This is remarkable, because while the Beats might’ve been the literary movement to become (justly or otherwise) synonymous with inevitable cultural change, Confessional poetry is synonymous with the inevitable democratization of poetry: the spread of the personal poem that proliferated with the rise of the photocopier and reached maturity on the Internet.

The term "Confessional" is inherently vague, which might account for some of the critical quiet. First used by M. L. Rosenthal in 1959 to describe the works of Robert Lowell, the term describes poetry that has a therapeutic purpose, for the author, in the writing, and typically, but not necessarily, relies heavily on the "I" word. Such a literary philosophy long predates 1959—I’ll argue that it includes most novels and all myth. Still, Lowell readily attached himself to the descriptor, associating it with literature’s natural changes in subject matter as American culture, confused about gender and terrified of technology, fractured. Confessional poetry became associated with psychosexual contemplations, solidifying into an emotional and "romantic" counterpoint to the open sexuality of the Beats and Hippies. Traditionally, women are more interested in such contemplations than men, and when two of Lowell’s students, Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton, became associated with the term, the jargon, illogically, solidified further: Confessional poetry became the poetry of not only women, but girls. If a non-poet knows the term "Confessional poetry," they very likely associate it with teenage girls. Thus might some of the term’s relative critical obscurity be described: no one wants to be a teenage girl.

This near-universal truth might be described as sexism, but it is not, itself, misogyny: it’s common sense. Girlhood, as this book makes clear, is dangerous and unhealthy. No sane person would ever want to be a teenage girl. Teenage girls live in circumstances which make sanity nearly impossible, but even when they are raised to be sane and can remain so, they exist in a state of constant physical and psychic peril. "Misogyny" can be defined as the way in which we are so ready to blame girls for their terrifying existence, and while our culture’s omnipresent misogyny is reprehensible, it is not actually surprising. Girlhood is a trauma so complete, yet so pervasive, that we are all forced to revisit it constantly. We do this with legitimate film and literature, but also passively, in every news report, in every advertisement, in every song and music video. The male who avoids reflecting on girlhood is perpetually assaulted by reminders of it, in a way that inevitably causes irrational response. Thus, misogyny (along with a fixation on youth) deepens and girlhood becomes more dangerous, creating a cycle that would threaten our species were there not so many cultural voices ready to combat it.

Such is the context in which the term Confessionalism is typically used or avoided, and such is the context of ASHES AND SEEDS. The book is, quite openly, a therapeutic exploration of the author’s girlhood. Unlikely Books, and its parent, the electronic magazine UnlikelyStories.org, has published a number of works on this topic. In several ways, ASHES AND SEEDS is the most traditional of these. The psychosexual relationships described here are essentially heteronormative. Gender and sexuality are not particularly experimental; the book is not overtly feminist (although it is obviously the product of an author who understands and appreciates feminist discourse). The poetic forms used are often quite contemporary, particularly the haibun: a combination of prose poem and haiku that, in its English-language incarnation, is very 21st Century, and collaged here with quotes from literature and pop lyrics. But the greater structure of the book is narrative: its three sections build an emotional autobiography in the manner of Lowell’s books—that is, in a 20th Century way. It is therapy, and it is storytelling: it is a straightforward attempt to share the author’s trauma in a way that allows the reader to examine their own.

Michelle’s choice of structure is particularly interesting given her age, and the technological and literary context in which she left girlhood. Born in 1982, she was a teenager when Internet literature became a serious phenomenon: UnlikelyStories.orgwas founded before her sixteenth birthday. She did not spend a moment of her adult life contemplating whether or not the Internet was worthy of her poems: it was widely considered a legitimate venue for publication before she had any adult works to publish. Good literature responds to the technology that surrounds it, and Michelle has created many fine works and collaborations that could not easily exist outside of our era, working in visual poetry and other digitally-dependent forms. (Even so, there have always been things about her work that were out-of-step with the Age of Memes: consider her dedication to dating her drafts, and publishing this information, a concept that seems antithetical to much Internet publishing, in which entire books, sometimes quite deliberately, completely disappear overnight.) Here, though, the intent is not experimental, but mythological. Like Anne Sexton, Michelle "lie[s] a lot" when offering direct descriptions of events: the autobiographical nature of this book is symbolic. Unlike Sexton, Michelle rarely uses the word "I."

I suggest that all myths, from Anansi to Spider-Man, begin with an individual’s attempt to describe their own existence in a universal (or at least very broad) way. Myths, after all, are guides and lessons. They might not be moral lessons, but they serve some instructional purpose: they describe life in an applicable way. Confessional poetry shares this intention, and the contemporary literary movements that reject Confessionalism tend to eschew, deliberately or otherwise, applicability: they sacrifice an author-reader connection in pursuit of beauty. In ASHES AND SEEDS, the context of the mythological lesson is very deliberate, and intertwined with Michelle’s choices in form. The central character that guides ASHES AND SEEDS is clearly an autobiographical construct, but she is not "I," but "she:" a named figure that changes coloration and identity, as both Everywoman and Other. She lives in a castle, in a mythical garden, at the origins of the universe—whether or not she simultaneously lives in Florida.

But make no mistake: this book is neither sermon nor lecture. There is no suggestion, in ASHES AND SEEDS, that people can, by behaving in a correct way, experience positive results: quite the opposite. Most clearly, the book says that girls suffer, but beyond that, do not look for predictable outcomes. Rather, look for direct experience, honest analysis of the experience, and the wisdom that can come from such self-study. Michelle, in a truly Confessional work, has chosen the forms, techniques, and symbols that most authentically (if not always literally) tell the story of her vanishing girlhood. Through this, we readers hope to absorb a piece of her experience, and learn lessons that cannot make us safe, but might make us stronger.